The horse (Equus ferus caballus)[2][3] is a domesticated, one-toed, hoofed mammal. It belongs to the taxonomic family Equidae and is one of two extant subspecies of Equus ferus. The horse has evolved over the past 45 to 55 million years from a small multi-toed creature, Eohippus, into the large, single-toed animal of today. Humans began domesticating horses around 4000 BCE, and their domestication is believed to have been widespread by 3000 BCE. Horses in the subspecies caballus are domesticated, although some domesticated populations live in the wild as feral horses. These feral populations are not true wild horses, which are horses that never have been domesticated. There is an extensive, specialized vocabulary used to describe equine-related concepts, covering everything from anatomy to life stages, size, colors, markings, breeds, locomotion, and behavior.

Horses are adapted to run, allowing them to quickly escape predators, and possess a good sense of balance and a strong fight-or-flight response. Related to this need to flee from predators in the wild is an unusual trait: horses are able to sleep both standing up and lying down, with younger horses tending to sleep significantly more than adults.[4] Female horses, called mares, carry their young for approximately 11 months and a young horse, called a foal, can stand and run shortly following birth. Most domesticated horses begin training under a saddle or in a harness between the ages of two and four. They reach full adult development by age five, and have an average lifespan of between 25 and 30 years.

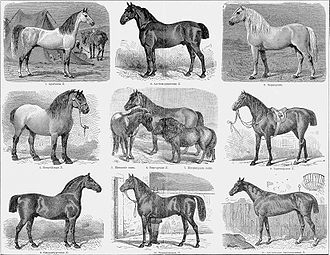

Horse breeds are loosely divided into three categories based on general temperament: spirited “hot bloods” with speed and endurance; “cold bloods”, such as draft horses and some ponies, suitable for slow, heavy work; and “warmbloods“, developed from crosses between hot bloods and cold bloods, often focusing on creating breeds for specific riding purposes, particularly in Europe. There are more than 300 breeds of horse in the world today, developed for many different uses.

Horses and humans interact in a wide variety of sport competitions and non-competitive recreational pursuits as well as in working activities such as police work, agriculture, entertainment, and therapy. Horses were historically used in warfare, from which a wide variety of riding and driving techniques developed, using many different styles of equipment and methods of control. Many products are derived from horses, including meat, milk, hide, hair, bone, and pharmaceuticals extracted from the urine of pregnant mares.

Biology

[edit]

Main article: Equine anatomy

Lifespan and life stages

[edit]

Depending on breed, management and environment, the modern domestic horse has a life expectancy of 25 to 30 years.[7] Uncommonly, a few animals live into their 40s and, occasionally, beyond.[8] The oldest verifiable record was “Old Billy“, a 19th-century horse that lived to the age of 62.[7] In modern times, Sugar Puff, who had been listed in Guinness World Records as the world’s oldest living pony, died in 2007 at age 56.[9]

Regardless of a horse or pony’s actual birth date, for most competition purposes a year is added to its age each January 1 of each year in the Northern Hemisphere[7][10] and each August 1 in the Southern Hemisphere.[11] The exception is in endurance riding, where the minimum age to compete is based on the animal’s actual calendar age.[12]

The following terminology is used to describe horses of various ages:FoalA horse of either sex less than one year old. A nursing foal is sometimes called a suckling, and a foal that has been weaned is called a weanling.[13] Most domesticated foals are weaned at five to seven months of age, although foals can be weaned at four months with no adverse physical effects.[14]YearlingA horse of either sex that is between one and two years old.[15]ColtA male horse under the age of four.[16] A common terminology error is to call any young horse a “colt”, when the term actually only refers to young male horses.[17]FillyA female horse under the age of four.[13]MareA female horse four years old and older.[18]StallionA non-castrated male horse four years old and older.[19] The term “horse” is sometimes used colloquially to refer specifically to a stallion.[20]GeldingA castrated male horse of any age.[13]

In horse racing, these definitions may differ: For example, in the British Isles, Thoroughbred horse racing defines colts and fillies as less than five years old.[21] However, Australian Thoroughbred racing defines colts and fillies as less than four years old.[22]

Size and measurement

[edit]

The height of horses is measured at the highest point of the withers, where the neck meets the back.[23] This point is used because it is a stable point of the anatomy, unlike the head or neck, which move up and down in relation to the body of the horse.

In English-speaking countries, the height of horses is often stated in units of hands and inches: one hand is equal to 4 inches (101.6 mm). The height is expressed as the number of full hands, followed by a point, then the number of additional inches, and ending with the abbreviation “h” or “hh” (for “hands high”). Thus, a horse described as “15.2 h” is 15 hands plus 2 inches, for a total of 62 inches (157.5 cm) in height.[24]

The size of horses varies by breed, but also is influenced by nutrition. Light-riding horses usually range in height from 14 to 16 hands (56 to 64 inches, 142 to 163 cm) and can weigh from 380 to 550 kilograms (840 to 1,210 lb).[25] Larger-riding horses usually start at about 15.2 hands (62 inches, 157 cm) and often are as tall as 17 hands (68 inches, 173 cm), weighing from 500 to 600 kilograms (1,100 to 1,320 lb).[26] Heavy or draft horses are usually at least 16 hands (64 inches, 163 cm) high and can be as tall as 18 hands (72 inches, 183 cm) high. They can weigh from about 700 to 1,000 kilograms (1,540 to 2,200 lb).[27]

The largest horse in recorded history was probably a Shire horse named Mammoth, who was born in 1848. He stood 21.2 1⁄4 hands (86.25 inches, 219 cm) high and his peak weight was estimated at 1,524 kilograms (3,360 lb).[28] The record holder for the smallest horse ever is Thumbelina, a fully mature miniature horse affected by dwarfism. She was 43 centimetres; 4.1 hands (17 in) tall and weighed 26 kg (57 lb).[29][30]

Ponies

[edit]

Main article: Pony

Ponies are taxonomically the same animals as horses. The distinction between a horse and pony is commonly drawn on the basis of height, especially for competition purposes. However, height alone is not dispositive; the difference between horses and ponies may also include aspects of phenotype, including conformation and temperament.

The traditional standard for height of a horse or a pony at maturity is 14.2 hands (58 inches, 147 cm). An animal 14.2 hands (58 inches, 147 cm) or over is usually considered to be a horse and one less than 14.2 hands (58 inches, 147 cm) a pony,[31]: 12 but there are many exceptions to the traditional standard. In Australia, ponies are considered to be those under 14 hands (56 inches, 142 cm).[32] For competition in the Western division of the United States Equestrian Federation, the cutoff is 14.1 hands (57 inches, 145 cm).[33] The International Federation for Equestrian Sports, the world governing body for horse sport, uses metric measurements and defines a pony as being any horse measuring less than 148 centimetres (58.27 in) at the withers without shoes, which is just over 14.2 hands (58 inches, 147 cm), and 149 centimetres (58.66 in; 14.2+1⁄2 hands), with shoes.[34]

Height is not the sole criterion for distinguishing horses from ponies. Breed registries for horses that typically produce individuals both under and over 14.2 hands (58 inches, 147 cm) consider all animals of that breed to be horses regardless of their height.[35] Conversely, some pony breeds may have features in common with horses, and individual animals may occasionally mature at over 14.2 hands (58 inches, 147 cm), but are still considered to be ponies.[36]

Ponies often exhibit thicker manes, tails, and overall coat. They also have proportionally shorter legs, wider barrels, heavier bone, shorter and thicker necks, and short heads with broad foreheads. They may have calmer temperaments than horses and also a high level of intelligence that may or may not be used to cooperate with human handlers.[31]: 11–12 [failed verification] Small size, by itself, is not an exclusive determinant. For example, the Shetland pony which averages 10 hands (40 inches, 102 cm), is considered a pony.[31]: 12 Conversely, breeds such as the Falabella and other miniature horses, which can be no taller than 76 centimetres; 7.2 hands (30 in), are classified by their registries as very small horses, not ponies.[37]

Genetics

[edit]

Horses have 64 chromosomes.[38] The horse genome was sequenced in 2007. It contains 2.7 billion DNA base pairs,[39] which is larger than the dog genome, but smaller than the human genome or the bovine genome.[40] The map is available to researchers.[41]

Colors and markings

[edit]

Main articles: Equine coat color, Equine coat color genetics, and Horse markings

Horses exhibit a diverse array of coat colors and distinctive markings, described by a specialized vocabulary. Often, a horse is classified first by its coat color, before breed or sex.[42] Horses of the same color may be distinguished from one another by white markings,[43] which, along with various spotting patterns, are inherited separately from coat color.[44]

Many genes that create horse coat colors and patterns have been identified. Current genetic tests can identify at least 13 different alleles influencing coat color,[45] and research continues to discover new genes linked to specific traits. The basic coat colors of chestnut and black are determined by the gene controlled by the Melanocortin 1 receptor,[46] also known as the “extension gene” or “red factor”.[45] Its recessive form is “red” (chestnut) and its dominant form is black.[47] Additional genes control suppression of black color to point coloration that results in a bay, spotting patterns such as pinto or leopard, dilution genes such as palomino or dun, as well as greying, and all the other factors that create the many possible coat colors found in horses.[45]

Horses that have a white coat color are often mislabeled; a horse that looks “white” is usually a middle-aged or older gray. Grays are born a darker shade, get lighter as they age, but usually keep black skin underneath their white hair coat (with the exception of pink skin under white markings). The only horses properly called white are born with a predominantly white hair coat and pink skin, a fairly rare occurrence.[47] Different and unrelated genetic factors can produce white coat colors in horses, including several different alleles of dominant white and the sabino-1 gene.[48] However, there are no “albino” horses, defined as having both pink skin and red eyes.[49]

Reproduction and development

[edit]

Main article: Horse breeding

Gestation lasts approximately 340 days, with an average range 320–370 days,[50][51] and usually results in one foal; twins are rare.[52] Horses are a precocial species, and foals are capable of standing and running within a short time following birth.[53] Foals are usually born in the spring. The estrous cycle of a mare occurs roughly every 19–22 days and occurs from early spring into autumn. Most mares enter an anestrus period during the winter and thus do not cycle in this period.[54] Foals are generally weaned from their mothers between four and six months of age.[55]

Horses, particularly colts, are sometimes physically capable of reproduction at about 18 months, but domesticated horses are rarely allowed to breed before the age of three, especially females.[31]: 129 Horses four years old are considered mature, although the skeleton normally continues to develop until the age of six; maturation also depends on the horse’s size, breed, sex, and quality of care. Larger horses have larger bones; therefore, not only do the bones take longer to form bone tissue, but the epiphyseal plates are larger and take longer to convert from cartilage to bone. These plates convert after the other parts of the bones, and are crucial to development.[56]

Depending on maturity, breed, and work expected, horses are usually put under saddle and trained to be ridden between the ages of two and four.[57] Although Thoroughbred race horses are put on the track as young as the age of two in some countries,[58] horses specifically bred for sports such as dressage are generally not put under saddle until they are three or four years old, because their bones and muscles are not solidly developed.[59] For endurance riding competition, horses are not deemed mature enough to compete until they are a full 60 calendar months (five years) old.[12]

Anatomy

[edit]

Main articles: Equine anatomy, Muscular system of the horse, Respiratory system of the horse, and Circulatory system of the horse

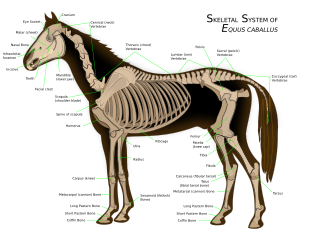

Skeletal system

[edit]

Main article: Skeletal system of the horse

The horse skeleton averages 205 bones.[60] A significant difference between the horse skeleton and that of a human is the lack of a collarbone—the horse’s forelimbs are attached to the spinal column by a powerful set of muscles, tendons, and ligaments that attach the shoulder blade to the torso. The horse’s four legs and hooves are also unique structures. Their leg bones are proportioned differently from those of a human. For example, the body part that is called a horse’s “knee” is actually made up of the carpal bones that correspond to the human wrist. Similarly, the hock contains bones equivalent to those in the human ankle and heel. The lower leg bones of a horse correspond to the bones of the human hand or foot, and the fetlock (incorrectly called the “ankle”) is actually the proximal sesamoid bones between the cannon bones (a single equivalent to the human metacarpal or metatarsal bones) and the proximal phalanges, located where one finds the “knuckles” of a human. A horse also has no muscles in its legs below the knees and hocks, only skin, hair, bone, tendons, ligaments, cartilage, and the assorted specialized tissues that make up the hoof.[61]

Hooves

[edit]

Main articles: Horse hoof, Horseshoe, and Farrier

The critical importance of the feet and legs is summed up by the traditional adage, “no foot, no horse”.[62] The horse hoof begins with the distal phalanges, the equivalent of the human fingertip or tip of the toe, surrounded by cartilage and other specialized, blood-rich soft tissues such as the laminae. The exterior hoof wall and horn of the sole is made of keratin, the same material as a human fingernail.[63] The result is that a horse, weighing on average 500 kilograms (1,100 lb),[64] travels on the same bones as would a human on tiptoe.[65] For the protection of the hoof under certain conditions, some horses have horseshoes placed on their feet by a professional farrier. The hoof continually grows, and in most domesticated horses needs to be trimmed (and horseshoes reset, if used) every five to eight weeks,[66] though the hooves of horses in the wild wear down and regrow at a rate suitable for their terrain.

Teeth

[edit]

Main article: Horse teeth

Horses are adapted to grazing. In an adult horse, there are 12 incisors at the front of the mouth, adapted to biting off the grass or other vegetation. There are 24 teeth adapted for chewing, the premolars and molars, at the back of the mouth. Stallions and geldings have four additional teeth just behind the incisors, a type of canine teeth called “tushes”. Some horses, both male and female, will also develop one to four very small vestigial teeth in front of the molars, known as “wolf” teeth, which are generally removed because they can interfere with the bit. There is an empty interdental space between the incisors and the molars where the bit rests directly on the gums, or “bars” of the horse’s mouth when the horse is bridled.[67]

An estimate of a horse’s age can be made from looking at its teeth. The teeth continue to erupt throughout life and are worn down by grazing. Therefore, the incisors show changes as the horse ages; they develop a distinct wear pattern, changes in tooth shape, and changes in the angle at which the chewing surfaces meet. This allows a very rough estimate of a horse’s age, although diet and veterinary care can also affect the rate of tooth wear.[7]

Digestion

[edit]

Main articles: Equine digestive system and Equine nutrition

Horses are herbivores with a digestive system adapted to a forage diet of grasses and other plant material, consumed steadily throughout the day. Therefore, compared to humans, they have a relatively small stomach but very long intestines to facilitate a steady flow of nutrients. A 450-kilogram (990 lb) horse will eat 7 to 11 kilograms (15 to 24 lb) of food per day and, under normal use, drink 38 to 45 litres (8.4 to 9.9 imp gal; 10 to 12 US gal) of water. Horses are not ruminants, having only one stomach, like humans. But unlike humans, they can digest cellulose, a major component of grass, through the process of hindgut fermentation. Cellulose fermentation by symbiotic bacteria and other microbes occurs in the cecum and the large intestine. Horses cannot vomit, so digestion problems can quickly cause colic, a leading cause of death.[68] Although horses do not have a gallbladder, they tolerate high amounts of fat in their diet.[69][70]

Senses

[edit]

See also: Equine vision

The horses’ senses are based on their status as prey animals, where they must be aware of their surroundings at all times.[71] The equine eye is one of the largest of any land mammal.[72] Horses are lateral-eyed, meaning that their eyes are positioned on the sides of their heads.[73] This means that horses have a range of vision of more than 350°, with approximately 65° of this being binocular vision and the remaining 285° monocular vision.[74] Horses have excellent day and night vision, but they have two-color, or dichromatic vision; their color vision is somewhat like red-green color blindness in humans, where certain colors, especially red and related colors, appear as a shade of green.[75]

Their sense of smell, while much better than that of humans, is not quite as good as that of a dog. It is believed to play a key role in the social interactions of horses as well as detecting other key scents in the environment. Horses have two olfactory centers. The first system is in the nostrils and nasal cavity, which analyze a wide range of odors. The second, located under the nasal cavity, are the vomeronasal organs, also called Jacobson’s organs. These have a separate nerve pathway to the brain and appear to primarily analyze pheromones.[76]

A horse’s hearing is good,[71] and the pinna of each ear can rotate up to 180°, giving the potential for 360° hearing without having to move the head.[77] Noise affects the behavior of horses and certain kinds of noise may contribute to stress—a 2013 study in the UK indicated that stabled horses were calmest in a quiet setting, or if listening to country or classical music, but displayed signs of nervousness when listening to jazz or rock music. This study also recommended keeping music under a volume of 21 decibels.[78] An Australian study found that stabled racehorses listening to talk radio had a higher rate of gastric ulcers than horses listening to music, and racehorses stabled where a radio was played had a higher overall rate of ulceration than horses stabled where there was no radio playing.[79]

Horses have a great sense of balance, due partly to their ability to feel their footing and partly to highly developed proprioception—the unconscious sense of where the body and limbs are at all times.[80] A horse’s sense of touch is well-developed. The most sensitive areas are around the eyes, ears, and nose.[81] Horses are able to sense contact as subtle as an insect landing anywhere on the body.[82]

Horses have an advanced sense of taste, which allows them to sort through fodder and choose what they would most like to eat,[83] and their prehensile lips can easily sort even small grains. Horses generally will not eat poisonous plants, however, there are exceptions; horses will occasionally eat toxic amounts of poisonous plants even when there is adequate healthy food.[84]

Movement

[edit]

Main articles: Horse gait, Trot, Canter, and Ambling

- Walk 5–8 km/h (3.1–5.0 mph)

- Trot 8–13 km/h (5.0–8.1 mph)

- Pace 8–13 km/h (5.0–8.1 mph)

- Canter 16–27 km/h (9.9–16.8 mph)

- Gallop 40–48 km/h (25–30 mph), record: 70.76 km/h (43.97 mph)

All horses move naturally with four basic gaits:[85]

- the four-beat walk, which averages 6.4 kilometres per hour (4.0 mph);

- the two-beat trot or jog at 13 to 19 kilometres per hour (8.1 to 11.8 mph) (faster for harness racing horses);

- the canter or lope, a three-beat gait that is 19 to 24 kilometres per hour (12 to 15 mph);

- the gallop, which averages 40 to 48 kilometres per hour (25 to 30 mph),[86] but the world record for a horse galloping over a short, sprint distance is 70.76 kilometres per hour (43.97 mph).[87]

Besides these basic gaits, some horses perform a two-beat pace, instead of the trot.[88] There also are several four-beat ‘ambling‘ gaits that are approximately the speed of a trot or pace, though smoother to ride. These include the lateral rack, running walk, and tölt as well as the diagonal fox trot.[89] Ambling gaits are often genetic in some breeds, known collectively as gaited horses.[90] These horses replace the trot with one of the ambling gaits.[91]

Behavior

[edit]

Main articles: Horse behavior and Stable vicesDuration: 3 seconds.0:03Horse neigh

Horses are prey animals with a strong fight-or-flight response. Their first reaction to a threat is to startle and usually flee, although they will stand their ground and defend themselves when flight is impossible or if their young are threatened.[92] They also tend to be curious; when startled, they will often hesitate an instant to ascertain the cause of their fright, and may not always flee from something that they perceive as non-threatening. Most light horse riding breeds were developed for speed, agility, alertness and endurance; natural qualities that extend from their wild ancestors. However, through selective breeding, some breeds of horses are quite docile, particularly certain draft horses.[93]

Horses are herd animals, with a clear hierarchy of rank, led by a dominant individual, usually a mare. They are also social creatures that are able to form companionship attachments to their own species and to other animals, including humans. They communicate in various ways, including vocalizations such as nickering or whinnying, mutual grooming, and body language. Many horses will become difficult to manage if they are isolated, but with training, horses can learn to accept a human as a companion, and thus be comfortable away from other horses.[94] However, when confined with insufficient companionship, exercise, or stimulation, individuals may develop stable vices, an assortment of bad habits, mostly stereotypies of psychological origin, that include wood chewing, wall kicking, “weaving” (rocking back and forth), and other problems.[95]

Intelligence and learning

[edit]

Studies have indicated that horses perform a number of cognitive tasks on a daily basis, meeting mental challenges that include food procurement and identification of individuals within a social system. They also have good spatial discrimination abilities.[96] They are naturally curious and apt to investigate things they have not seen before.[97] Studies have assessed equine intelligence in areas such as problem solving, speed of learning, and memory. Horses excel at simple learning, but also are able to use more advanced cognitive abilities that involve categorization and concept learning. They can learn using habituation, desensitization, classical conditioning, and operant conditioning, and positive and negative reinforcement.[96] One study has indicated that horses can differentiate between “more or less” if the quantity involved is less than four.[98]

Domesticated horses may face greater mental challenges than wild horses, because they live in artificial environments that prevent instinctive behavior whilst also learning tasks that are not natural.[96] Horses are animals of habit that respond well to regimentation, and respond best when the same routines and techniques are used consistently. One trainer believes that “intelligent” horses are reflections of intelligent trainers who effectively use response conditioning techniques and positive reinforcement to train in the style that best fits with an individual animal’s natural inclinations.[99]

Temperament

[edit]

Main articles: Draft horse, Warmblood, Oriental horse, and Hot-blooded horse

Horses are mammals. As such, they are warm-blooded, or endothermic creatures, as opposed to cold-blooded, or poikilothermic animals. However, these words have developed a separate meaning in the context of equine terminology, used to describe temperament, not body temperature. For example, the “hot-bloods“, such as many race horses, exhibit more sensitivity and energy,[100] while the “cold-bloods”, such as most draft breeds, are quieter and calmer.[101] Sometimes “hot-bloods” are classified as “light horses” or “riding horses”,[102] with the “cold-bloods” classified as “draft horses” or “work horses”.[103]

“Hot blooded” breeds include “oriental horses” such as the Akhal-Teke, Arabian horse, Barb, and now-extinct Turkoman horse, as well as the Thoroughbred, a breed developed in England from the older oriental breeds.[100] Hot bloods tend to be spirited, bold, and learn quickly. They are bred for agility and speed.[104] They tend to be physically refined—thin-skinned, slim, and long-legged.[105] The original oriental breeds were brought to Europe from the Middle East and North Africa when European breeders wished to infuse these traits into racing and light cavalry horses.[106][107]

Muscular, heavy draft horses are known as “cold bloods.” They are bred not only for strength, but also to have the calm, patient temperament needed to pull a plow or a heavy carriage full of people.[101] They are sometimes nicknamed “gentle giants”.[108] Well-known draft breeds include the Belgian and the Clydesdale.[108] Some, like the Percheron, are lighter and livelier, developed to pull carriages or to plow large fields in drier climates.[109] Others, such as the Shire, are slower and more powerful, bred to plow fields with heavy, clay-based soils.[110] The cold-blooded group also includes some pony breeds.[111]

“Warmblood” breeds, such as the Trakehner or Hanoverian, developed when European carriage and war horses were crossed with Arabians or Thoroughbreds, producing a riding horse with more refinement than a draft horse, but greater size and milder temperament than a lighter breed.[112] Certain pony breeds with warmblood characteristics have been developed for smaller riders.[113] Warmbloods are considered a “light horse” or “riding horse”.[102]

Today, the term “Warmblood” refers to a specific subset of sport horse breeds that are used for competition in dressage and show jumping.[114] Strictly speaking, the term “warm blood” refers to any cross between cold-blooded and hot-blooded breeds.[115] Examples include breeds such as the Irish Draught or the Cleveland Bay. The term was once used to refer to breeds of light riding horse other than Thoroughbreds or Arabians, such as the Morgan horse.[104]

Sleep patterns

[edit]

See also: Horse sleep patterns and Sleep in non-humans

Horses are able to sleep both standing up and lying down. In an adaptation from life in the wild, horses are able to enter light sleep by using a “stay apparatus” in their legs, allowing them to doze without collapsing.[116] Horses sleep better when in groups because some animals will sleep while others stand guard to watch for predators. A horse kept alone will not sleep well because its instincts are to keep a constant eye out for danger.[117]

Unlike humans, horses do not sleep in a solid, unbroken period of time, but take many short periods of rest. Horses spend four to fifteen hours a day in standing rest, and from a few minutes to several hours lying down. Total sleep time in a 24-hour period may range from several minutes to a couple of hours,[117] mostly in short intervals of about 15 minutes each.[118] The average sleep time of a domestic horse is said to be 2.9 hours per day.[119]

Horses must lie down to reach REM sleep. They only have to lie down for an hour or two every few days to meet their minimum REM sleep requirements.[117] However, if a horse is never allowed to lie down, after several days it will become sleep-deprived, and in rare cases may suddenly collapse because it slips, involuntarily, into REM sleep while still standing.[120] This condition differs from narcolepsy, although horses may also suffer from that disorder.[121]

Taxonomy and evolution

[edit]

Main articles: Evolution of the horse, Equus (genus), and Equidae

The horse adapted to survive in areas of wide-open terrain with sparse vegetation, surviving in an ecosystem where other large grazing animals, especially ruminants, could not.[122] Horses and other equids are odd-toed ungulates of the order Perissodactyla, a group of mammals dominant during the Tertiary period. In the past, this order contained 14 families, but only three—Equidae (the horse and related species), Tapiridae (the tapir), and Rhinocerotidae (the rhinoceroses)—have survived to the present day.[123]

The earliest known member of the family Equidae was the Hyracotherium, which lived between 45 and 55 million years ago, during the Eocene period. It had 4 toes on each front foot, and 3 toes on each back foot.[124] The extra toe on the front feet soon disappeared with the Mesohippus, which lived 32 to 37 million years ago.[125] Over time, the extra side toes shrank in size until they vanished. All that remains of them in modern horses is a set of small vestigial bones on the leg below the knee,[126] known informally as splint bones.[127] Their legs also lengthened as their toes disappeared until they were a hooved animal capable of running at great speed.[126] By about 5 million years ago, the modern Equus had evolved.[128] Equid teeth also evolved from browsing on soft, tropical plants to adapt to browsing of drier plant material, then to grazing of tougher plains grasses. Thus proto-horses changed from leaf-eating forest-dwellers to grass-eating inhabitants of semi-arid regions worldwide, including the steppes of Eurasia and the Great Plains of North America.

By about 15,000 years ago, Equus ferus was a widespread holarctic species. Horse bones from this time period, the late Pleistocene, are found in Europe, Eurasia, Beringia, and North America.[129] Yet between 10,000 and 7,600 years ago, the horse became extinct in North America.[130][131][132] The reasons for this extinction are not fully known, but one theory notes that extinction in North America paralleled human arrival.[133] Another theory points to climate change, noting that approximately 12,500 years ago, the grasses characteristic of a steppe ecosystem gave way to shrub tundra, which was covered with unpalatable plants.[134]

Wild species surviving into modern times

[edit]

Main article: Wild horse

A truly wild horse is a species or subspecies with no ancestors that were ever successfully domesticated. Therefore, most “wild” horses today are actually feral horses, animals that escaped or were turned loose from domestic herds and the descendants of those animals.[135] Only two wild subspecies, the tarpan and the Przewalski’s horse, survived into recorded history and only the latter survives today.

The Przewalski’s horse (Equus ferus przewalskii), named after the Russian explorer Nikolai Przhevalsky, is a rare Asian animal. It is also known as the Mongolian wild horse; Mongolian people know it as the taki, and the Kyrgyz people call it a kirtag. The subspecies was presumed extinct in the wild between 1969 and 1992, while a small breeding population survived in zoos around the world. In 1992, it was reestablished in the wild by the conservation efforts of numerous zoos.[136] Today, a small wild breeding population exists in Mongolia.[137][138] There are additional animals still maintained at zoos throughout the world.

Their status as a truly wild horse was called into question when domestic horses of the 5,000-year-old Botai culture of Central Asia were found to be more closely related to Przewalski’s horses than to E. f. caballus. The study raised the possibility that modern Przewalski’s horses could be the feral descendants of the domestic Botai horses. The study concluded that the Botai animals appear to have been an independent domestication attempt and apparently unsuccessful in terms of genetic markers carrying through to modern domesticated equines. However, the question of whether all Przewalski’s horses descend from this population is also unresolved, as only one of seven modern Przewalski’s horses in the study shared this ancestry. It may also be that both the Botai horses and the modern Przewalski’s horses descend separately from the same ancient wild Przewalski’s horse population.[139][140][141]

The tarpan or European wild horse (Equus ferus ferus) was found in Europe and much of Asia. It survived into the historical era, but became extinct in 1909, when the last captive died in a Russian zoo.[142] Thus, the genetic line was lost. Attempts have been made to recreate the tarpan,[142][143][144] which resulted in horses with outward physical similarities, but nonetheless descended from domesticated ancestors and not true wild horses.

Periodically, populations of horses in isolated areas are speculated to be relict populations of wild horses, but generally have been proven to be feral or domestic. For example, the Riwoche horse of Tibet was proposed as such,[138] but testing did not reveal genetic differences from domesticated horses.[145] Similarly, the Sorraia of Portugal was proposed as a direct descendant of the Tarpan on the basis of shared characteristics,[146][147] but genetic studies have shown that the Sorraia is more closely related to other horse breeds, and that the outward similarity is an unreliable measure of relatedness.[146][148]

Other modern equids

[edit]

Main article: Equus (genus)

Besides the horse, there are six other species of genus Equus in the Equidae family. These are the ass or donkey, Equus asinus; the mountain zebra, Equus zebra; plains zebra, Equus quagga; Grévy’s zebra, Equus grevyi; the kiang, Equus kiang; and the onager, Equus hemionus.[149]

Horses can crossbreed with other members of their genus. The most common hybrid is the mule, a cross between a “jack” (male donkey) and a mare. A related hybrid, a hinny, is a cross between a stallion and a “jenny” (female donkey).[150] Other hybrids include the zorse, a cross between a zebra and a horse.[151] With rare exceptions, most hybrids are sterile and cannot reproduce.[152]

Domestication and history

[edit]

Main articles: History of horse domestication theories and Domestication of the horse

Domestication of the horse most likely took place in central Asia prior to 3500 BCE. Two major sources of information are used to determine where and when the horse was first domesticated and how the domesticated horse spread around the world. The first source is based on palaeological and archaeological discoveries; the second source is a comparison of DNA obtained from modern horses to that from bones and teeth of ancient horse remains.

The earliest archaeological evidence for attempted domestication of the horse comes from sites in Ukraine and Kazakhstan, dating to approximately 4000–3500 BCE.[153][154][155] However the horses domesticated at the Botai culture in Kazakhstan were Przewalski’s horses and not the ancestors of modern horses.[156][157]

By 3000 BCE, the horse was completely domesticated and by 2000 BCE there was a sharp increase in the number of horse bones found in human settlements in northwestern Europe, indicating the spread of domesticated horses throughout the continent.[158] The most recent, but most irrefutable evidence of domestication comes from sites where horse remains were interred with chariots in graves of the Indo-European Sintashta and Petrovka cultures c. 2100 BCE.[159]

A 2021 genetic study suggested that most modern domestic horses descend from the lower Volga-Don region. Ancient horse genomes indicate that these populations influenced almost all local populations as they expanded rapidly throughout Eurasia, beginning about 4,200 years ago. It also shows that certain adaptations were strongly selected due to riding, and that equestrian material culture, including Sintashta spoke-wheeled chariots spread with the horse itself.[160][157]

Domestication is also studied by using the genetic material of present-day horses and comparing it with the genetic material present in the bones and teeth of horse remains found in archaeological and palaeological excavations. The variation in the genetic material shows that very few wild stallions contributed to the domestic horse,[161][162] while many mares were part of early domesticated herds.[148][163][164] This is reflected in the difference in genetic variation between the DNA that is passed on along the paternal, or sire line (Y-chromosome) versus that passed on along the maternal, or dam line (mitochondrial DNA). There are very low levels of Y-chromosome variability,[161][162] but a great deal of genetic variation in mitochondrial DNA.[148][163][164] There is also regional variation in mitochondrial DNA due to the inclusion of wild mares in domestic herds.[148][163][164][165] Another characteristic of domestication is an increase in coat color variation.[166] In horses, this increased dramatically between 5000 and 3000 BCE.[167]

Before the availability of DNA techniques to resolve the questions related to the domestication of the horse, various hypotheses were proposed. One classification was based on body types and conformation, suggesting the presence of four basic prototypes that had adapted to their environment prior to domestication.[111] Another hypothesis held that the four prototypes originated from a single wild species and that all different body types were entirely a result of selective breeding after domestication.[168] However, the lack of a detectable substructure in the horse has resulted in a rejection of both hypotheses.

Feral populations

[edit]

Main article: Feral horse

Feral horses are born and live in the wild, but are descended from domesticated animals.[135] Many populations of feral horses exist throughout the world.[169][170] Studies of feral herds have provided useful insights into the behavior of prehistoric horses,[171] as well as greater understanding of the instincts and behaviors that drive horses that live in domesticated conditions.[172]

There are also semi-feral horses in many parts of the world, such as Dartmoor and the New Forest in the UK, where the animals are all privately owned but live for significant amounts of time in “wild” conditions on undeveloped, often public, lands. Owners of such animals often pay a fee for grazing rights.[173][174]

Breeds

[edit]

Main articles: Horse breed, List of horse breeds, and Horse breeding

The concept of purebred bloodstock and a controlled, written breed registry has come to be particularly significant and important in modern times. Sometimes purebred horses are incorrectly or inaccurately called “thoroughbreds”. Thoroughbred is a specific breed of horse, while a “purebred” is a horse (or any other animal) with a defined pedigree recognized by a breed registry.[175] Horse breeds are groups of horses with distinctive characteristics that are transmitted consistently to their offspring, such as conformation, color, performance ability, or disposition. These inherited traits result from a combination of natural crosses and artificial selection methods. Horses have been selectively bred since their domestication. An early example of people who practiced selective horse breeding were the Bedouin, who had a reputation for careful practices, keeping extensive pedigrees of their Arabian horses and placing great value upon pure bloodlines.[176] These pedigrees were originally transmitted via an oral tradition.[177]

Breeds developed due to a need for “form to function”, the necessity to develop certain characteristics in order to perform a particular type of work.[178] Thus, a powerful but refined breed such as the Andalusian developed as riding horses with an aptitude for dressage.[178] Heavy draft horses were developed out of a need to perform demanding farm work and pull heavy wagons.[179] Other horse breeds had been developed specifically for light agricultural work, carriage and road work, various sport disciplines, or simply as pets.[180] Some breeds developed through centuries of crossing other breeds, while others descended from a single foundation sire, or other limited or restricted foundation bloodstock. One of the earliest formal registries was General Stud Book for Thoroughbreds, which began in 1791 and traced back to the foundation bloodstock for the breed.[181] There are more than 300 horse breeds in the world today.[182]

Interaction with humans

[edit]

Worldwide, horses play a role within human cultures and have done so for millennia. Horses are used for leisure activities, sports, and working purposes. The Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) estimates that in 2008, there were almost 59,000,000 horses in the world, with around 33,500,000 in the Americas, 13,800,000 in Asia and 6,300,000 in Europe and smaller portions in Africa and Oceania. There are estimated to be 9,500,000 horses in the United States alone.[183] The American Horse Council estimates that horse-related activities have a direct impact on the economy of the United States of over $39 billion, and when indirect spending is considered, the impact is over $102 billion.[184] In a 2004 “poll” conducted by Animal Planet, more than 50,000 viewers from 73 countries voted for the horse as the world’s 4th favorite animal.[185]

Communication between human and horse is paramount in any equestrian activity;[186] to aid this process horses are usually ridden with a saddle on their backs to assist the rider with balance and positioning, and a bridle or related headgear to assist the rider in maintaining control.[187] Sometimes horses are ridden without a saddle,[188] and occasionally, horses are trained to perform without a bridle or other headgear.[189] Many horses are also driven, which requires a harness, bridle, and some type of vehicle.[190]

Sport

[edit]

Main articles: Equestrianism, Horse racing, Horse training, and Horse tack

Historically, equestrians honed their skills through games and races. Equestrian sports provided entertainment for crowds and honed the excellent horsemanship that was needed in battle. Many sports, such as dressage, eventing, and show jumping, have origins in military training, which were focused on control and balance of both horse and rider. Other sports, such as rodeo, developed from practical skills such as those needed on working ranches and stations. Sport hunting from horseback evolved from earlier practical hunting techniques.[186] Horse racing of all types evolved from impromptu competitions between riders or drivers. All forms of competition, requiring demanding and specialized skills from both horse and rider, resulted in the systematic development of specialized breeds and equipment for each sport. The popularity of equestrian sports through the centuries has resulted in the preservation of skills that would otherwise have disappeared after horses stopped being used in combat.[186]

Horses are trained to be ridden or driven in a variety of sporting competitions. Examples include show jumping, dressage, three-day eventing, competitive driving, endurance riding, gymkhana, rodeos, and fox hunting.[191] Horse shows, which have their origins in medieval European fairs, are held around the world. They host a huge range of classes, covering all of the mounted and harness disciplines, as well as “In-hand” classes where the horses are led, rather than ridden, to be evaluated on their conformation. The method of judging varies with the discipline, but winning usually depends on style and ability of both horse and rider.[192] Sports such as polo do not judge the horse itself, but rather use the horse as a partner for human competitors as a necessary part of the game. Although the horse requires specialized training to participate, the details of its performance are not judged, only the result of the rider’s actions—be it getting a ball through a goal or some other task.[193] Examples of these sports of partnership between human and horse include jousting, in which the main goal is for one rider to unseat the other,[194] and buzkashi, a team game played throughout Central Asia, the aim being to capture a goat carcass while on horseback.[193]

Horse racing is an equestrian sport and major international industry, watched in almost every nation of the world. There are three types: “flat” racing; steeplechasing, i.e. racing over jumps; and harness racing, where horses trot or pace while pulling a driver in a small, light cart known as a sulky.[195] A major part of horse racing’s economic importance lies in the gambling associated with it.[196]

Work

[edit]

Horse pulling a cart

A mounted police officer in Poland

There are certain jobs that horses do very well, and no technology has yet developed to fully replace them. For example, mounted police horses are still effective for certain types of patrol duties and crowd control.[197] Cattle ranches still require riders on horseback to round up cattle that are scattered across remote, rugged terrain.[198] Search and rescue organizations in some countries depend upon mounted teams to locate people, particularly hikers and children, and to provide disaster relief assistance.[199] Horses can also be used in areas where it is necessary to avoid vehicular disruption to delicate soil, such as nature reserves. They may also be the only form of transport allowed in wilderness areas. Horses are quieter than motorized vehicles. Law enforcement officers such as park rangers or game wardens may use horses for patrols, and horses or mules may also be used for clearing trails or other work in areas of rough terrain where vehicles are less effective.[200]

Although machinery has replaced horses in many parts of the world, an estimated 100 million horses, donkeys and mules are still used for agriculture and transportation in less developed areas. This number includes around 27 million working animals in Africa alone.[201] Some land management practices such as cultivating and logging can be efficiently performed with horses. In agriculture, less fossil fuel is used and increased environmental conservation occurs over time with the use of draft animals such as horses.[202][203] Logging with horses can result in reduced damage to soil structure and less damage to trees due to more selective logging.[204]

Warfare

[edit]

Main article: Horses in warfare

Horses have been used in warfare for most of recorded history. The first archaeological evidence of horses used in warfare dates to between 4000 and 3000 BCE,[205] and the use of horses in warfare was widespread by the end of the Bronze Age.[206][207] Although mechanization has largely replaced the horse as a weapon of war, horses are still seen today in limited military uses, mostly for ceremonial purposes, or for reconnaissance and transport activities in areas of rough terrain where motorized vehicles are ineffective. Horses have been used in the 21st century by the Janjaweed militias in the War in Darfur.[208]

Entertainment and culture

[edit]

See also: Horse symbolism, Horses in art, and Horse worship

Modern horses are often used to reenact many of their historical work purposes. Horses are used, complete with equipment that is authentic or a meticulously recreated replica, in various live action historical reenactments of specific periods of history, especially recreations of famous battles.[209] Horses are also used to preserve cultural traditions and for ceremonial purposes. Countries such as the United Kingdom still use horse-drawn carriages to convey royalty and other VIPs to and from certain culturally significant events.[210] Public exhibitions are another example, such as the Budweiser Clydesdales, seen in parades and other public settings, a team of draft horses that pull a beer wagon similar to that used before the invention of the modern motorized truck.[211]

Horses are frequently used in television, films and literature. They are sometimes featured as a major character in films about particular animals, but also used as visual elements that assure the accuracy of historical stories.[212] Both live horses and iconic images of horses are used in advertising to promote a variety of products.[213] The horse frequently appears in coats of arms in heraldry, in a variety of poses and equipment.[214] The mythologies of many cultures, including Greco-Roman, Hindu, Islamic, and Germanic, include references to both normal horses and those with wings or additional limbs, and multiple myths also call upon the horse to draw the chariots of the Moon and Sun.[215] The horse also appears in the 12-year cycle of animals in the Chinese zodiac related to the Chinese calendar.[216]

Horses serve as the inspiration for many modern automobile names and logos, including the Ford Pinto, Ford Bronco, Ford Mustang, Hyundai Equus, Hyundai Pony, Mitsubishi Starion, Subaru Brumby, Mitsubishi Colt/Dodge Colt, Pinzgauer, Steyr-Puch Haflinger, Pegaso, Porsche, Rolls-Royce Camargue, Ferrari, Carlsson, Kamaz, Corre La Licorne, Iran Khodro, Eicher, and Baojun.[217][218][219] Indian TVS Motor Company also uses a horse on their motorcycles & scooters.

Therapeutic use

[edit]

See also: Equine-assisted therapy and Therapeutic horseback riding

People of all ages with physical and mental disabilities obtain beneficial results from an association with horses. Therapeutic riding is used to mentally and physically stimulate disabled persons and help them improve their lives through improved balance and coordination, increased self-confidence, and a greater feeling of freedom and independence.[220] The benefits of equestrian activity for people with disabilities has also been recognized with the addition of equestrian events to the Paralympic Games and recognition of para-equestrian events by the International Federation for Equestrian Sports (FEI).[221] Hippotherapy and therapeutic horseback riding are names for different physical, occupational, and speech therapy treatment strategies that use equine movement. In hippotherapy, a therapist uses the horse’s movement to improve their patient’s cognitive, coordination, balance, and fine motor skills, whereas therapeutic horseback riding uses specific riding skills.[222]

Horses also provide psychological benefits to people whether they actually ride or not. “Equine-assisted” or “equine-facilitated” therapy is a form of experiential psychotherapy that uses horses as companion animals to assist people with mental illness, including anxiety disorders, psychotic disorders, mood disorders, behavioral difficulties, and those who are going through major life changes.[223] There are also experimental programs using horses in prison settings. Exposure to horses appears to improve the behavior of inmates and help reduce recidivism when they leave.[224]

Products

[edit]

Horses are raw material for many products made by humans throughout history, including byproducts from the slaughter of horses as well as materials collected from living horses.

Products collected from living horses include mare’s milk, used by people with large horse herds, such as the Mongols, who let it ferment to produce kumis.[225] Horse blood was once used as food by the Mongols and other nomadic tribes, who found it a convenient source of nutrition when traveling. Drinking their own horses’ blood allowed the Mongols to ride for extended periods of time without stopping to eat.[225] The drug Premarin is a mixture of estrogens extracted from the urine of pregnant mares (pregnant mares’ urine), and was previously a widely used drug for hormone replacement therapy.[226] The tail hair of horses can be used for making bows for string instruments such as the violin, viola, cello, and double bass.[227]

Horse meat has been used as food for humans and carnivorous animals throughout the ages. Approximately 5 million horses are slaughtered each year for meat worldwide.[228] It is eaten in many parts of the world, though consumption is taboo in some cultures,[229] and a subject of political controversy in others.[230] Horsehide leather has been used for boots, gloves, jackets,[231] baseballs,[232] and baseball gloves. Horse hooves can also be used to produce animal glue.[233] Horse bones can be used to make implements.[234] Specifically, in Italian cuisine, the horse tibia is sharpened into a probe called a spinto, which is used to test the readiness of a (pig) ham as it cures.[235] In Asia, the saba is a horsehide vessel used in the production of kumis.[236]

Care

[edit]

Main article: Horse care

See also: Equine nutrition, Horse grooming, Veterinary medicine, and Farrier

Horses are grazing animals, and their major source of nutrients is good-quality forage from hay or pasture.[237] They can consume approximately 2% to 2.5% of their body weight in dry feed each day. Therefore, a 450-kilogram (990 lb) adult horse could eat up to 11 kilograms (24 lb) of food.[238] Sometimes, concentrated feed such as grain is fed in addition to pasture or hay, especially when the animal is very active.[239] When grain is fed, equine nutritionists recommend that 50% or more of the animal’s diet by weight should still be forage.[240]

Horses require a plentiful supply of clean water, a minimum of 38 to 45 litres (10 to 12 US gal) per day.[241] Although horses are adapted to live outside, they require shelter from the wind and precipitation, which can range from a simple shed or shelter to an elaborate stable.[242]

Horses require routine hoof care from a farrier, as well as vaccinations to protect against various diseases, and dental examinations from a veterinarian or a specialized equine dentist.[243] If horses are kept inside in a barn, they require regular daily exercise for their physical health and mental well-being.[244] When turned outside, they require well-maintained, sturdy fences to be safely contained.[245] Regular grooming is also helpful to help the horse maintain good health of the hair coat and underlying skin.[246]

Climate change

[edit]

This section is an excerpt from Effects of climate change on livestock § Equines.[edit]

As of 2019, there are around 17 million horses in the world. Healthy body temperature for adult horses is in the range between 37.5 and 38.5 °C (99.5 and 101.3 °F), which they can maintain while ambient temperatures are between 5 and 25 °C (41 and 77 °F). However, strenuous exercise increases core body temperature by 1 °C (1.8 °F)/minute, as 80% of the energy used by equine muscles is released as heat. Along with bovines and primates, equines are the only animal group which use sweating as their primary method of thermoregulation: in fact, it can account for up to 70% of their heat loss, and horses sweat three times more than humans while undergoing comparably strenuous physical activity. Unlike humans, this sweat is created not by eccrine glands but by apocrine glands.[248] In hot conditions, horses during three hours of moderate-intensity exercise can lose 30 to 35 L of water and 100g of sodium, 198 g of choloride and 45 g of potassium.[248] In another difference from humans, their sweat is hypertonic, and contains a protein called latherin,[249] which enables it to spread across their body easier, and to foam, rather than to drip off. These adaptations are partly to compensate for their lower body surface-to-mass ratio, which makes it more difficult for horses to passively radiate heat. Yet, prolonged exposure to very hot and/or humid conditions will lead to consequences such as anhidrosis, heat stroke, or brain damage, potentially culminating in death if not addressed with measures like cold water applications. Additionally, around 10% of incidents associated with horse transport have been attributed to heat stress. These issues are expected to worsen in the future.[247]African horse sickness (AHS) is a viral illness with a mortality close to 90% in horses, and 50% in mules. A midge, Culicoides imicola, is the primary vector of AHS, and its spread is expected to benefit from climate change.[250] The spillover of Hendra virus from its flying fox hosts to horses is also likely to increase, as future warming would expand the hosts’ geographic range. It has been estimated that under the “moderate” and high climate change scenarios, RCP4.5 and RCP8.5, the number of threatened horses would increase by 110,000 and 165,000, respectively, or by 175 and 260%.[251]